Logs 2020-05-11: Sequences of Sets

Here’s a quick little math one.

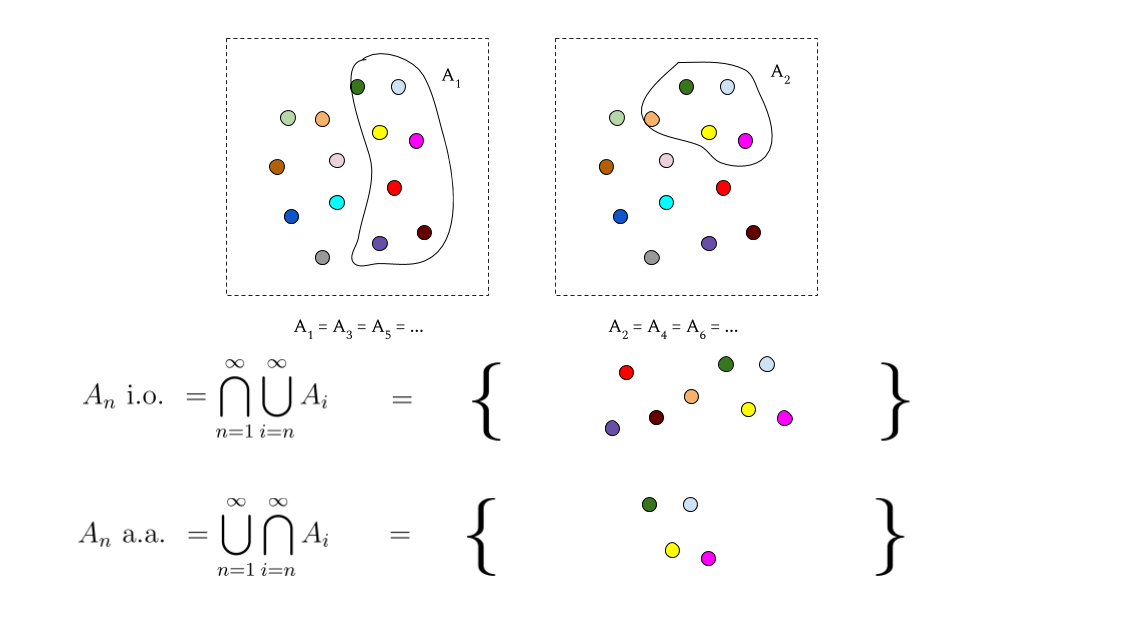

In a probability theory class that I was sitting in on, one of the core concepts taught was the limit infimum and limit supremum of a sequence of sets. If An is a sequence of sets (that are all subsets of some larger set E) then the two constructs are also known as An almost always and An infinitely often respectively. They are formally defined as follows:

lim infn→∞=An a.a.=∞⋃n=1∞⋂k=nAk

lim supn→∞=An i.o.=∞⋂n=1∞⋃k=nAk

When I saw these for the first time it was tough for me to connect the semantics of the concepts to the unions and intersections of the formal definition. I’ll try to impart a bit of intuition now that I think I’ve gotten a better grasp of it.

For a.a.: first, focus on each inner intersection, ⋂∞k=nAk. Hell, we can even give each of these a name, say, Bn. So, we have, for all elements in e∈E, that ∃n,e∈⋂∞k=nAn⟹e∈An a.a. That is, if e is in any Bn then it’s in An a.a.

Now, we can see here that due to how we know intersection works, once e is in Bn then it’s definitely in every Bm for m≥n. The key thing to consider here for intuition are each of the cases when an element e∈Bm but e∉Bm−1. In this case, we know that e is in every Ak,∀k≥m but is not in Am−1. In fact, An a.a. is just a collection of all of the elements for which this happens at some point.

The most memorable intuition for me is that An a.a. is the set of all elements in E that appear in all but finitely many of the An.

For i.o.: I like to see this as the union of all An with things sheared off from it as the outer intersection works its course. This outer intersection goes to infinity; all elements in An i.o. are in every single union ⋃∞k=nAk,∀n (in the same vein as the above call these Cn). As we’re thinking of things being sheared off, the intuition here is to think of the things that are absent from the set: if, at any point, an element e ceases to be present in a Cn, then it cannot be in the whole intersection (by the way that our unions work, if e∉Cn then e∉Cm∀m≥n). What worked for me at this point was to think of An i.o. as all elements e for which, ∀N∈N,∃n≥N,e∈An — if you “look past” any particular N, one of the sets that exist past that point is bound to contain the element e.

Analogous to how the limsup is greater than or equal to the liminf for a sequence of numbers, An i.o.⊇An a.a..

Hopefully this was informative! I originally tried to make a visual explanation but it got messy and sort of failed: